|

|

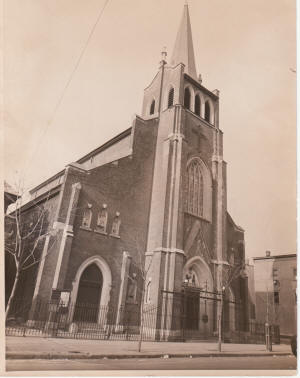

Gót és római

stílus keveréke, a középhajó hossza 100 láb, szélessége

65 láb. A középhajó magassága 60 láb, a mellékhajók

magassága 27 láb. A hajó 14 vas oszlopon nyugszik.

Minden második oszlopfón, ahol az ívek nem találkoznak,

egy-egy mellszobor áll, a latin és görög egyházdoktorok

szobrai. Az oszlopfők -- a templom fődíszessége—az olasz

építőmester eredeti eszméje után cementből készültek.

Minden oszlopfőről három szárnyas angyal tekint le.

Valamennyi különböző. Az első tervrajz szerint a

vasoszlopokat csak faburkolatok vették körül és az

oszlopfők is egész egyszerüek voltak.

A szentély

középpontja a gyönyörü gótikus főoltár, tervét Ft.

Messerschmidt készítette, míg Schimmel Anton, tiroli

származású képfaragó faragta. Magassága 40 láb,

szélessége 18 láb. Ez híveinknek egyik büszkesége. A

tabernakulum felett Szt. István óriási szobrát látjuk,

amint a Szent Koronát a Magyarok Nagyasszonyának

felajánlja. Tőle jobbra és balra az Árpádházi

szentjeinket, Szt. Imre herceget, Szt. László királyt,

és kisebb alakban Szt. Erzsébet asszonyt és Szt. Margit

szüzet találjuk. A főoltár a Szt. Anna Egylet ajándéka,

az ára $1,359.00. 1904. július 26-án, Szt. Anna napján

áldotta meg Ft. Haintinger Imre, helybeli plébános. A szentély

középpontja a gyönyörü gótikus főoltár, tervét Ft.

Messerschmidt készítette, míg Schimmel Anton, tiroli

származású képfaragó faragta. Magassága 40 láb,

szélessége 18 láb. Ez híveinknek egyik büszkesége. A

tabernakulum felett Szt. István óriási szobrát látjuk,

amint a Szent Koronát a Magyarok Nagyasszonyának

felajánlja. Tőle jobbra és balra az Árpádházi

szentjeinket, Szt. Imre herceget, Szt. László királyt,

és kisebb alakban Szt. Erzsébet asszonyt és Szt. Margit

szüzet találjuk. A főoltár a Szt. Anna Egylet ajándéka,

az ára $1,359.00. 1904. július 26-án, Szt. Anna napján

áldotta meg Ft. Haintinger Imre, helybeli plébános.

A templom három

hajójú. A kórussal együtt 500 ember számára elegendő. A

szentély jobb és bal oldalán egy-egy ajtó visz a

sekrestyékbe. A szószék a szentélyben áll s a baloldali

sekrestyéből vezet fel rá a lépcső. A kórus felé eső

rész a három hajónak megfelelőleg -- három előcsarnokból

áll -- a jobb- és baloldaliból vezetnek a lépcsők a

kórusra. Az előcsarnokok mellett mindkét oldalon egy-egy

gyóntatószék volt, ma a Hősök oltára és a Missziós

Kereszt van ott.

A templomnak

padokra is volt szüksége, de csak 1906-ban tudták azokat

beszerezni. Addig bérelt padok álltak rendelkezésre.

A mellékoltárok is

müvészi alkotások. A jobb oldali Jézus Szíve, a

baloldali Szüz Mária tiszteletére van szentelve. Csak

hét évvel később, 1910, július hóban került rájuk a sor.

Költsége $1,100.00 volt. A Jézus Szíve

mellékoltárt használja most is a pap Nagypénteken mint "Szentsír",

a magyar cserkészek állnak a Szent Sír elött sírőrséget.

A Jézus Szíve szobrot az 1990-es évek elején

restaurálták. A Szüz Mária oltárt ma is ünnepélyesen

díszítik fel, a Szent Szüz szobrát minden év májusában

megkoronázzák.

A torony magassága

132 láb. Három harang hírdeti naponként Isten dicsőségét.

A negyedik harang a temetéseken használt gyászharang.

1958-ban valósult meg végre Messerschmidt Atya álma,

hogy három harang szólal meg a templomunk tornyából.

Ekkor avatták fel az u.n. szabadság harangot. 2001-ben

javították meg a harangokat, több lelkes egyházközségi

tag jóvoltából. Most egész Passaicon lehet hallani a

déli harangszót, amely megemlékezik az 1456-os

Nándorfehérvári győzelemről.

Az ablakaink külön

kincsei templomunknak. Az eredeti ablakokat, mint a

templom egész belsejét Messerschmidt Atya tervezte. Azok

az ablakok tiszta átlátszóak voltak és a lehető legtöbb

fényt hoztak be a templomba. A 14 színesen festett ablak,

amely körbeveszi a templomot, különböző jeleneteket idéz

elő a Szentírásból, valamint a szentek életéből. Ezek az

ablakok kb. 16 láb magasak. Az oltár feletti és orgona

feletti ablakok is elösegitik a fény besugárzását a

templomunkba. Ezeket a színes ablakokat Gáspár Atya

ideje alatt kapta a templom.

Két szószék

szolgálta plébánosainkat 100 év alatt. Az eredeti

szószék egy magas érő, müvészien faragott gótikus munka

volt. Gáspár János Atya ideje alatt alacsonyabbra

alakitották át. A második, mostani szószék az 1950-es

években készült el. Az akkori, Kertész László által írt,

igen népszerü egyházi színdarabok bevételéből fedezték

az egyházközségi tagok.

A falakon volt a

keresztút 14 gipszből készített állomása. Ezeket a régi

dombormüveket az 1940-es évek alatt kicserélték,

bronzból készültekre majd az 1990-es évek végén

restaurálták.

A templomot

eredetileg gázzal és villannyal világították és fütötték.

Gázlámpák és gyertyák lógtak a magas oszlopokról. Azokat

leszereltették, amikor új fütés és lámpa berendezést

kapott a templom az 1950-es években.

A templomban

nagyon sok szobor van. A főoltáron levő Árpádházi magyar

szenteken és az oszlopok tetején álló mellszobrokon

kívül, a világ közkedvelt szentjei közül sokan vannak a

templomban megörökítve. Lisieuxi Szent Teréz a Hősök

oltára mellett áll rózsafüzérrel és rózsáival. A

Missziós Kereszt alatt található Michelangelo Pietájának

szobra. A többi szobor kiegészíti a templom áhitat- és

esztetihai kaértékét.

Az orgona a

Vermont Peragallo n. cégtől van. 1953 óta használ a

templom villannyal müködő orgonát. Az orgonának kilenc

csősora van és variált zenei hangokat tud utánozni. Az

orgona az 1990-es években lett restaurálva, azóta

hangverseny keretében többször is játszották helybeli

müvészek. Orgonistáink vasárnaponként, ünnepeken,

esküvőkön és temetéseken az orgona zenéjével emelik a

szentmise áhitatát.

A templom alatti termek különböző célokat szolgáltak az

évszázad során. Az 1920-as és 30-as években ott tartott

a templom kántora, id. Molnár András, hittanoktatást,

valamint magyar nyelv oktatást a gyerekeknek.

Raktározásra és cserkész összejövetelekre használták

évtizedeken keresztül. 1997-ben nagy templomi takarítást

rendeztek. Két hatalmas nagy termet nyert ezzel a

templom. Azóta gyülésteremnek használják, alkalmadtán

zenei és irodalmi előadásoknak a helyszíne.

Megjegyzés: 1 láb = 30,48 cm

A

Szent István templomban komoly művészi értékek

találhatók, melyeket sokáig fel sem ismertünk. Gaetano

Federicinek, a XX. század kiemelkedő amerikai

szobrászának nyolc mellszobra díszíti a templom

főhajóját, négy-négy szobor a két szembenálló fal

oszlopfőin. A művek a keleti és nyugati egyházak nyolc

egyházdoktorát ábrázolják.

Federici 1880-ban született az olaszországi

Castelgrandeban, és hétéves korában került Amerikába,

ahol édesapjának sikeres építkezési vállalkozása volt. Ő

építette a mi templomunkat is. Fia viszont páratlan

művészi tehetsége birtokában a templom belső díszítését

végezte. Stílusa hagyományos, klasszicista volt, az

abban az időben dúló avantgarde irányzatokkal

szembefordulva.

Egyik tanára a manhattani, Giuseppe Moretti volt, aki a

St. Louis-i Világkiállításra az alabamai Birmingham

város rendelésére egy óriási méretű,Vulkánt ábrázoló

szobrot tervezett. Mivel műterme nem bizonyult elég

nagynak, az akkor épülő templomunkban készítette al a 17

méter magas szobor életnagyságú modelljét. A mű óriási

méretét jelzi a végleges, kiöntött szobor 54 tonna súlya.

Morettinak érdekes módon már azelőtt is volt magyar

kapcsolata: Ferenc Józsefről márvány portrét készített,

dolgozott Budapesten is, és Erdélyben kitűnő márványt

talált, de kitermelését a katonai hatóságok nem

engedélyezték (az orosz betöréstől félve nem építették

ki a szükséges vasútvonalat). Az alábbi két angolnyelvű

cikk közül az első bemutatja Federicit, a második pedig

a Vulkán szobor történetét írja le.

Gaetano Federici

In front of St. John's Cathedral in Paterson stands a

statue of Irish priest Dean William McNulty, comforting

a barefoot orphan boy. The statue, completed in 1923,

has come to symbolize nationally the pastoral role of

priests in a working-class city like Paterson. It is

also one of the best-known works of sculptor Gaetano

Federici, whose outdoor sculptures abound in Paterson

and other parts of North Jersey.

Federici died in 1964, at the age of 84, leaving a

legacy of hundreds of public works. Federici, Paterson's

unofficial “sculptor laureate,” was one of New Jersey's

few native sculptors, according to one expert, and an

extraordinarily prolific one. The Encyclopedia of

American Biography in 1966 called Federici “an

outstanding American sculptor... who won international

acclaim for his work.”

Gaetano Federici At least 40 of Federici's major statues

are within two miles of Paterson's City Hall. Federici's

sculptures also are found in Cuba, New York, Hollywood,

and in churches and cemeteries throughout the region.

Our church houses eight Federici-busts. Meredith Bzdak

New Jersey art his-torian said the Federici Studio

Collection represents the majority of Federici's life

work. “I feel the studio collec-tion should remain

intact – because it is one of the only collections of

its kind. And because of the significance of Federici to

us,” she said.

Fiorina said she remembered her grandfather as always at

work in his studio. She has family snapshots of him, a

short, sprightly man with a carefully trimmed goatee and

a beret. The pictures are of a grandfatherly figure

smiling warmly into the camera while working on huge

figures in his studio.

Gaetano Federici was born in Castelgrande, on the slopes

of the southern Italian Apennines in 1880. In 1887, he

and his mother left their mountainous village to join

his father, Antonio, in Paterson. Antonio Federici was a

stone mason who had become a successful contractor in

the booming industrial city. One of his works is our own

church. Federici showed artistic promise as a Paterson

High School student. By that time, his father could

afford to allow the boy to get artistic training. As a

young man Federici was apprenticed to some of the

leading sculptors of his time. He studied in New York

with the Art Students League. At the young age of 24, he

sculptured the eight busts of the Doctors of the Church

in our church on top of the 30-foot pillars.

Federici was trained in the academic tradition and would

never stray far from it. Experts called him a

conservative sculptor: While European sculptors were

doing avant-garde work, Federici stayed with classical

themes. He was painstaking in his attention to detail,

yet always attempted to capture the personality of the

subject.

Based on an article by Joseph D. McCaffrey, Star-Ledger

Staff, March 14, 1997

Vulcan in St. Stephen's Church

Some thought a great saint was being built for the

church, and they crossed themselves as they approached.

But all were awed by the grandeur and majesty of the

figure, and their exclamations of wonder and surprise

were good evidence of the impression it made upon their

minds.

This quote from the Newark Daily described the situation

in St. Stephen's during the winter of 1903–1904. From

December to January, the Italian sculptor Giuseppe

Moretti used the unfinished church to produce a

fifty-six-foot full-size model of his statue of Vulcan.

His New York studio was not large enough for this

immense sculpture commissioned by the Commercial Club of

Birmingham. Moretti was the mentor of Frederici, who, at

the time, was decorating our church with his works.

Fred M. Jackson, Sr. became president of the Commercial

Club in 1903. The Club's purpose was to “invest in the

future of the city”, and Jackson saw great opportunity

in the St. Louis World's Fair of 1904. He and fellow

club member James A. MacKnight envisioned sending a

great statue of the Roman god Vulcan, a smith, armorer,

architect, chariot builder and artist, to the fair. The

time left was short, however, making it difficult to

find a sculptor who would take the job, but erecting a

giant statue in record time would be great glory for

Birmingham. After some searching and refusals MacKnight

finally found a suitable sculptor – Giuseppe Moretti.

Giuseppe Moretti was born in Siena, Italy in 1857. He

had considered a career in the opera but decided on

sculpting, and at the age of fifteen he went to Florence

to continue his education in sculpting. Here he became

especially interested in marble sculpture and soon moved

to Carrara, the marble center of Italy, to continue

developing his skill. Around 1879 he moved to Agram,

Croatia, and set up his own shop there. He completed

several important pieces before a great earthquake

devastated the city and ruined his work. He then went to

Vienna where he was commissioned to make a marble

portrait of the Emperor Franz Josef, which was exhibited

in 1889 at the Paris exposition, and to design

sculptures for the Rothschild palace. He traveled to

Budapest next, where he executed some pieces

commemorating the city's history. He discovered an

excellent source of statuary marble in Transylvania, but

his hopes of quarrying it were not realized. At the

advice of the Germans, the government did not allow a

railroad to be built to the site as planned, because

this would help the Russians if they invaded the area.

Thus Moretti left Europe for the United States, where he

would have freedom in the artistic and business aspects

of his career. After arriving in New York in 1888, he

designed and made several large sculptures in

Pittsburgh.

Moretti offered to sculpt the enormous Vulcan in forty

days for $6,000. He got the job and began after some

controversy about the appearance of the statue: Moretti

planned to stay true to the myths and portray Vulcan as

a strong but not very good-looking god. The Birmingham

Commercial Club wanted a handsome statue. In the end,

Moretti won and went to work. He began in his studio on

152 West Thirty-eighth Street in New York. Here he made

the eight-foot working clay statue of the god. He then

had to make the fifty-six-foot, full-size clay model –

but where would he find room? He located a space big

enough: the unfinished St. Stephen's Church of Passaic,

New Jersey. One of his pupils, Gaetano Federici was

working on the church under contruction, hence the

connection. In December 1903, with the help of sixteen

assistants, he made the enormous clay model. It was so

cold and drafty in the unfinished St. Stephen's that

parts of the head and posterior had to be repaired

because they had frozen.

In January and February the parts were shipped down by

railroad to Alabama, where they were cast in iron. Then

it was shipped to St. Louis in pieces:

“As Vulcan neared completion in late May, visitors

craned their necks to view this giant reaching fifty-six

feet from pedestal to spear tip. His shoulders measured

ten feet in width, and his chest nearly twenty-three

feet in circumference. Moretti had deliberately

distorted the statue's proportions, giving more mass to

the head, shoulders, and chest, so that when viewed from

below, the body would appear in correct proportion. The

entire statue, including hammer and anvil block, was

estimated to weigh some 120,000 pounds. In September

1904, Vulcan surprised no one by being awarded the Grand

Prize for best exhibit in the Mineral Department of the

fair. Another tribute to Alabama came when Signor

Moretti was awarded a silver medal for his Head of

Christ, a bust sculpted from Alabama marble, with which

Moretti had become quite impressed during his stay in

the state.” (Thompson)

After the fair, Vulcan was shipped back to Birmingham in

pieces, but problems arose about where to erect the

statue. For two years the pieces lay by the railroad

while arguments went on. Finally the President of the

State Fair Association, Culpepper Exum, offered a place

for Vulcan at the fairgrounds. Here, however, workmen

incorrectly installed both his right hand and left arm,

so that he could not grasp his spear or hammer, and he

stood like this for almost thirty years. He was even

used for advertising – at one point he even had a pair

of blue jeans painted on. At last in the 1930s two

members of Birmingham's Kiwanis Club, Thomas Joy and J.

Mercer Barnett, gave him a decent home in Red Mountain.

Thad Holt, state director for the Works Progress

Administration, began construction on Vulcan Park. Soon

Vulcan stood on a 124-foot pedestal of native sandstone.

In 1946 he became a symbol of highway safety: on his

spear a neon torch shines green, except during times of

a traffic fatality, when it glows red. In the 1960s his

tower received a makeover. Recently, however, there were

problems with the statue itself. Back in the 1930s when

Vulcan was first placed on his tower, workers filled his

cavity up to the shoulders with concrete to “stabilize”

it. Because of the different expansion rates of concrete

and iron, the statue began to crack. About two years

ago, a large campaign in Birmingham initiated the

restoration of the statue. At present Vulcan is taken

apart and is being repaired. The goal is to restore

Vulcan, the stone pedestal and the park by 2004, his

100th birthday.

Klára Felsővályi

Sources:

The Vulcan Restoration by J. Scott Howell

http://www.robinson-iron.com/pages/vulcanproject2a.html

http://www.geocities.com/freeindeed_john836/Part5.html

Giuseppe Moretti by Jennifer M. Willard

http://www.bham.lib.al.us/Archives/oldsite/giuseppemoretti.htm

Vulcan: Birmingham’s Man of Iron by George Clinton

Thompson

http://www.bplonline.org/Archives/oldsite/vulcanbirminghamsmanofiron.htm

|

![]()